St. Oswald’s, Grasmere and Dove Cottage

Page Guide

- History of the Church

- St. Oswalds for the Wordsworths

- Memorials for the Wordsworth Family

- Wordsworth Family Graves

- Poems and Writing Relevant to St. Oswald’s Grasmere

History of St. Oswald’s

Located in the Lake District of Cumbria in the village of Grasmere, St. Oswald’s Church was named for the Northumbrian king and champion, killed at Maserfield at a battle with Penda in 642 AD. Originally the church was modest, consisting of only a tower and a nave.

St. Oswald’s for the Wordsworths

During their residence at Dove Cottage, the church’s rectory had fallen into disrepair as Dorothy remarks in her journal, noting the “ugly white wall” enclosing the rectory’s courtyard.

The church’s interior was sparse–on earthen floors with rushes sat the congregation’s benches. A wood and charcoal heating system was installed in 1810. Men and women entered via separate doors.

In December 1799, William, then age 29, brought his sister Dorothy, then age 27, to Grasmere where the Church of St. Oswald serves as a focal point of village life (3). Together, they would make Dove Cottage their first home since their parents’ deaths. Residence at Grasmere gave William and Dorothy the space and time to fully realize their relationships, including “their [deep] affection for each other” and common “interests and outlook.”

To speak to how Dove Cottage impacted William Wordsworth’s work, William mentions Dove Cottage in “The Waggoner”:

‘At the bottom of the brow, Where once the Dove and Olive Bough Offered a greeting of good ale To all who entered Grasmere Vale; And called on him who must depart To leave it with a jovial heart; There, where the Dove and Olive Bough Once hung, a poet harbours now A simple water-drinking Bard.’

William also composed “Ode on Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood” at Dove Cottage with a view of garden and windows:

‘The rainbow comes and goes, and lovely is the rose, The moon does with delight Look round her when the heavens are bare’ Waters on a starry night Are beautiful and fair; The Sunshine is glorious birth; But yet I know, where’er I go, That there hath passed away a glory from the earth.’

Dorothy triangulates St. Oswald’s and Dove Cottage as she describes a local woman’s funeral that occurred on September 3rd, 1800, specifically how the funeralgoers carried the coffin from a near a duck-pond, past Dove Cottage while singing a psalm,

“When we came to the bridge, they began to sing again, but stopped during four lines before they entered the Churchyard. The priest met us – he did not look as a man ought to on such an occasion – I had seen him half-drunk the day before in a pot-house. Before we came with the corpse, one of the company observed he wondered what sort of cue our parson would be in! N.B. It was the day after the Fair.’”

For the better part of their time in Grasmere, the siblings seldom attended church. In fact, during that period Dorothy’s journal only references churchgoing twice and both occasions are when William is not at home:

May 18th 1800, “Went to Church, slight showers a cold air.”

A fortnight later, “Rain in the night – a sweet mild morning. Read Ballads. Went to Church. Singers from Wythburn; went part of the way home with Miss Simpson. Walked upon the hill above the house till dinner-time – went again to Church – Christening and singing, which kept us very late. The pew-side came down with me.”

In a letter, William writes of another congregation, giving us insight into St. Oswald’s culture:

“We were pleased with the singing; and I have often heard a far worse person – I mean as to reading. His sermon was, to be sure, as village sermons often are, very injudicious; a most knowing discourse about the Gnostics, and other hard names of those who were ‘adversaries of Christianity and enemies of the Gospel…the girls were not well-dressed. Their clothes were indeed clean, but not tidy; they were in this respect a shocking contrast to our congregation in Grasmere.”

In ‘The Excursion,’’ Book V, Wordsworth pictures the church as it stands today:

Not raised in nice proportions,’ but ‘large and massy, for duration built; With pillars crowded, and the roof upheld By naked rafters intricately crossed….. The floor Of nave and aisle, in unpretending guise, Was occupied by oaken benches, ranged In seemly rows….. A copious pew Of sculptured oak stood there, with drapery line.’

After their move to Rydal Mount in 1813, The Wordsworths frequented the Grasmere church most Sundays. During this period, the church received greater care with regular white washing, new pews and a stone floor to replace the benches and rushes, and repairs to the cracked church bell and tower clock. The final renovation included the installation of a pitch pipe. In 1819, William planted eight of the existing yews in the churchyard.

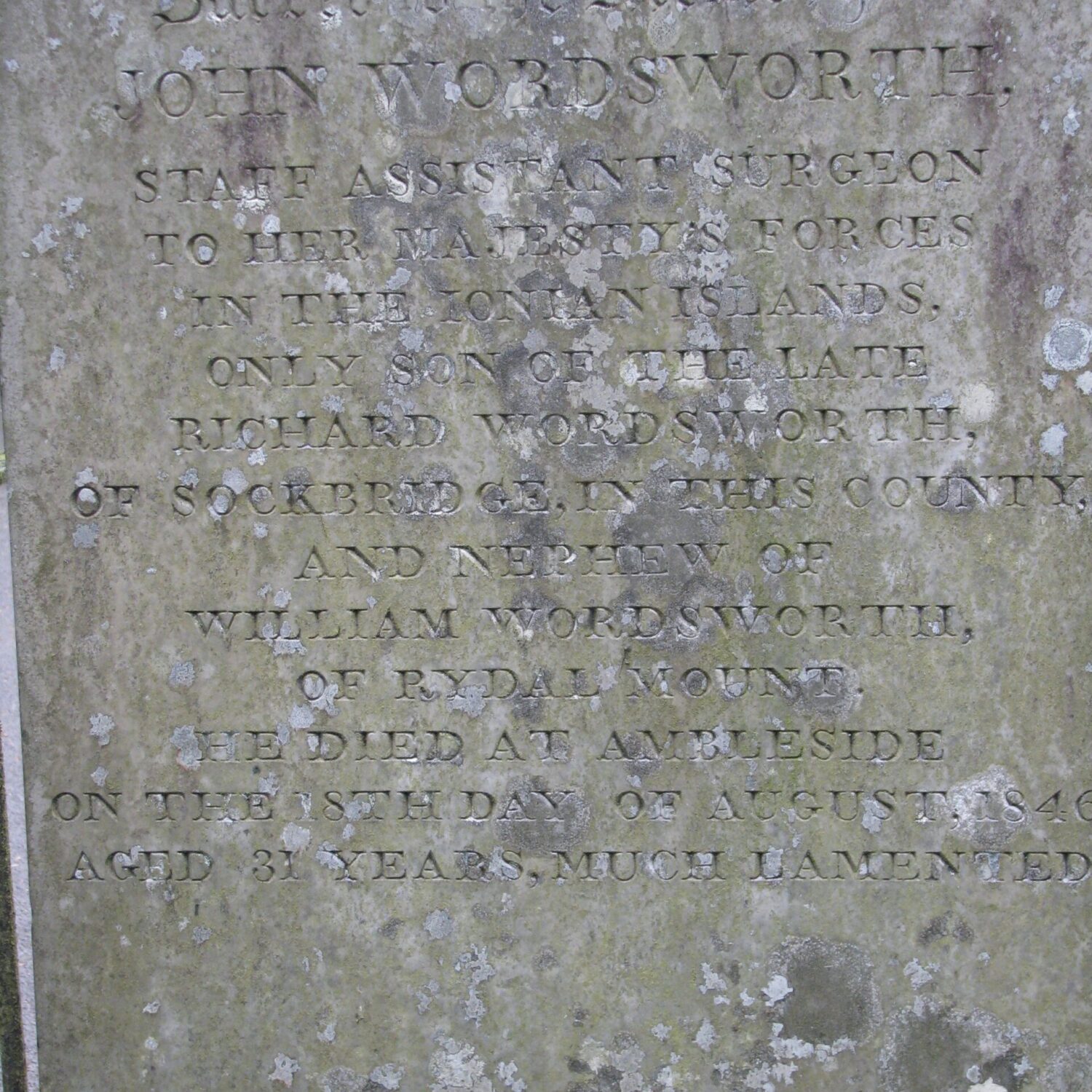

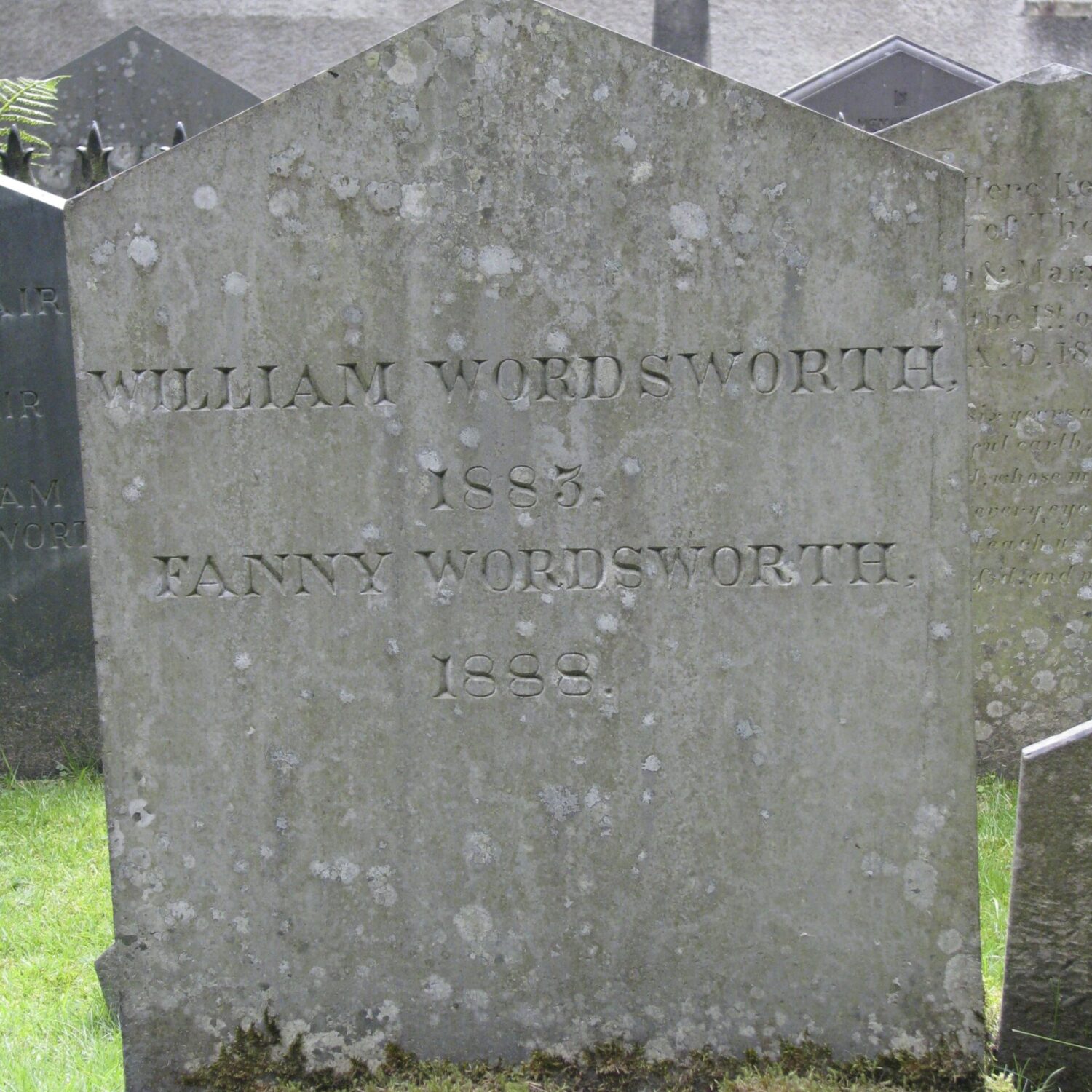

Memorials for the Wordsworth Family

A simple slate stone marks the grave of William Wordsworth (1850) and Mary Wordsworth (1859). To the north lies Dora, the daughter of William and Mary, to the south lies Dorothy, William’s sister. West of Dorothy lay Catherine and Thomas, William’s children who died in 1812 at the Rectory. Hartley Coleridge, son of Samuel Taylor Coleridge lies not far from the Wordsworth family.

The Wordsworth Family Graves

By Polly Atkin

These writings fit many of the basic premises of grave tourism that were arising in this period. In The Literary Tourist, Nicola Watson writes convincingly of a growing thanatocentricism in nineteenth-century tourism, leading to a kind of grave tourism, whereby ‘grave visiting is imagined as a way of by-passing the text in favour of more perfect dialogue with the dead author.’1 This is linked to what Anthony Vidler identifies as ‘the fantasies of burial and return that were inseparable from the historical and archaeological self-consciousness of the nineteenth century.’2 The grave, as the final residence of the writer, could be perceived to be more likely to guarantee a spectral encounter than the home. As Matthews argues

The burial place […] has a peculiar claim to authenticity as the site most directly connected to the poet, through the physical remains of the corpse: the poet as biographical entity is in some sense still present, a few feet under the surface of grass or stone.

However there is also a more basic, practical reason for the growth of grave-visiting as literary tourism increases in popularity: in the majority of cases the grave is a public place, readily accessibly to any number of tourists without cost.

Matthews notes the popularity of Wordsworth’s grave as touristic destination in the years directly after his death, seeing it as the inevitable outcome of his own work. However, for Stopford Brooke and his fellow Wordsworthians in the 1880s, the grave, as repository only of the mortal remains, is a poor substitute for access to the site of poetic production, and poetic vitality. At this time, Brooke laments, ‘there is no place, indeed, intimately associated with Wordsworth, which is open, except the Churchyard where he is buried.’1 It is presumably partly the allure of Wordsworth’s grave that drew Brooke and his brother to Grasmere in the summer of 1889. Grasmere at this time is already a station on a nascent Wordsworth trail. In his pamphlet on Dove Cottage, Brooke notes:

This is clearly first-hand knowledge. Many of these tourists may have been following the suggestions of guides such as Black’s, or Jenkinson’s Practical Guide to the English Lake District (first published in 1872), which posits:

“Many persons will enjoy spending a quiet Sunday at Grasmere, and, after attending the church, hallowed by so many associations, and visiting the poet’s grave, will delight to saunter in the neighbourhood with ‘The Excursion’ as a companion, or a volume of the lyrical poems.”

In the 1878 first edition of William Knight’s The English Lake District as Interpreted in the Poems of Wordsworth, Grasmere is given its own chapter because it is ‘where he is buried’, and the churchyard and ‘The Excursion’ are given sixteen pages.1 In the illustrated quarto Through the Wordsworth Country (1887), Knight, like Wordsworth, repeats his descriptions, stating ‘there are few spots in England more peaceful, or more sacred’ than Grasmere churchyard The churchyard is not only ‘sacred to the memory of Wordsworth’, but hallowed by the interment also of ‘his wife (Mary Hutchinson), his sister Dorothy, their daughter Dora (Mrs Quillinan), and their two children who died in infancy, [who] lie together under the shade of one of the yew-trees which the poet planted.’ This is substantiated for Knight by ‘the grave of Hartley Coleridge […] close at hand.’ Together, these associations, in Knight’s conception, make Grasmere churchyard holier than ‘Weimar or Florence […] Athens of Rome, or Westminster Abbey’, or ‘Stratford-Upon-Avon [which] has associations with the Mightier Dead’. None of these places, Knight claims, ‘evok[e] a deeper feeling than that which rises in the heart of the pilgrim who reverently visits the churchyard of Grasmere.’Knight, quoting the Excursion, laments in ‘Through the Wordsworth Country’, the church yard

was in the poet’s time, “almost wholly free From interruption of sepulchral stones.” It is not so now.

Grasmere churchyard offers a connection not only with the poet through the physical presence of his decaying remains, but through his imaginative and physical input into the place itself. As Knight presents it, Wordsworth’s grave offered a more complete touristic experience than most, as not only final home, but a site written about by the poet, a site of emotional significance to the poet (as location of his loved ones’ graves), and a site physically moulded by the poet (through the planting of the yew trees). The yew trees act as a symbol of the continuing effect of Wordsworth’s presence in the world after death (as they continue to grow).1 Wordsworthian pilgrims to Grasmere churchyard could thus simultaneously imagine themselves in supernatural conversation with the dead poet, in the landscape of one of his poems, and in a landscape both formed by him and chosen as special.

Poems and Writing Relevant to St. Oswald’s Grasmere

- Waggoner

- The Excursion

- Ode on Intimations of immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood

- Dorothy Wordsworth’s Grasmere Journal

References

Brooke, Stopford A. Dove Cottage: Wordsworth’s Home from 1800-1808, December 21, 1799 to May-, 1808. Macmillan, 1924.

Grasmere Church, Kay Jay Print Ltd., Cross Hills.

Hendrix, Harald. “From Early Modern to Romantic Literary Tourism: A Diachronical Perspective.” Literary Tourism and Nineteenth- Century Culture, 2009, pp. 13–24., https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230234109_2.

Jenkinson, Henry Irwin, and Edward Stanford. Practical Guide to the English Lake District. Edward Stanford, 55 Charing Cross, S.W., 1881.

KNIGHT, William Angus, and William Wordsworth. The English Lake District as Interpreted in the Poems of Wordsworth … Third Edition. Edinburgh, 1904.

Knight, William, and Harry Goodwin. Through the Wordsworth Country. S. Sonnenschein, 1887.

Matthews, Samantha. “Making Their Mark: Writing the Poet’s Grave.” Literary Tourism and Nineteenth- Century Culture, 2009, pp. 25–36., https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230234109_3.

Taylor, E. Margaret. William Wordsworth and St. Oswald’s Church, Grasmere, Kay Jay Print Ltd, Grasmere Church Publications, Cross Hills, 2004.

Vidler, Anthony. The Architectural Uncanny: Essays in the Modern Unhomely. MIT Press, 1999.

Watson, Nicola J. The Literary Tourist: Readers and Places in Romantic & Victorian Britain. Palgrave Macmillan, 2008.